Columnist: The tragedy of a lynching; relatives of the victim seek closure

Published 12:00 am Saturday, September 12, 2015

Seventy-five years ago on Sept. 8, 1940, a 16-year-old black male was shot and killed by a lynch mob in a rural community called Liberty Hill, outside of LaGrange. His name was Austin Callaway.

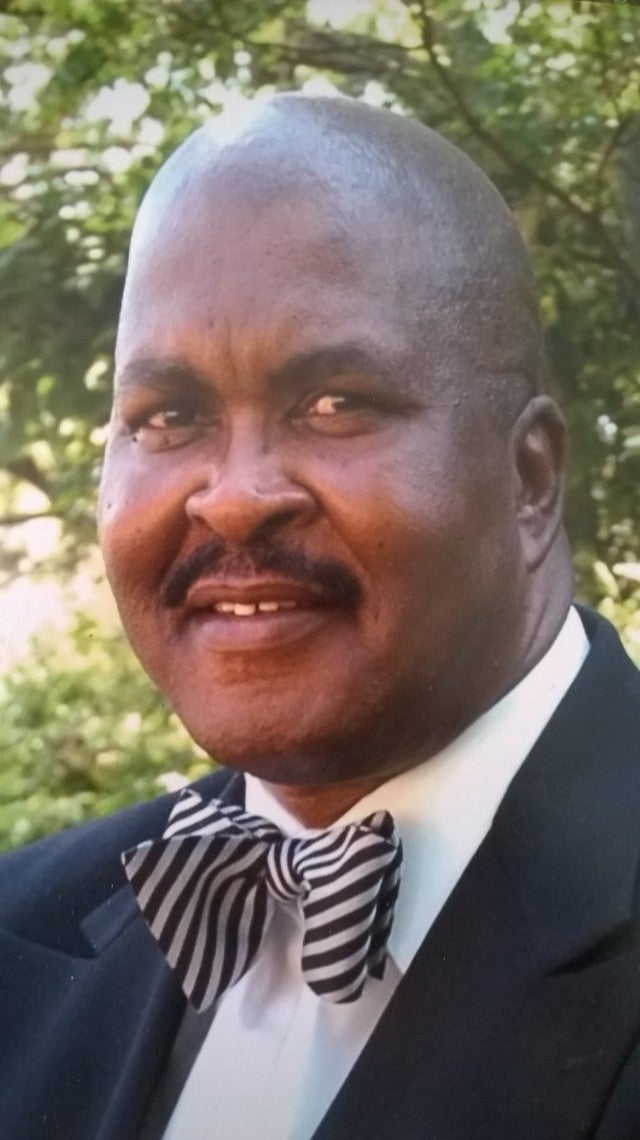

Local residents Deborah Jones-Tatum, Frances Callaway-Jones and other relatives of the young man believe that it is about time for LaGrange to address this tragedy that was not, in their opinion, seriously investigated in 1940 by Sheriff E. V. Hillyer and the chief of police, J. E. Matthews, who were in charge of the investigation of Callaway’s death.

In fact, no report of any official investigation has ever been made public, resulting in the family believing that one never actually took place.

There are a few things, however, that are known about the lynching. One day before his murder, he was accused of attempted assault on a white woman. He was apprehended and placed in the local jail.

It was there that a jailer was allegedly forced to open the cell, allowing six white men wearing masks to kidnap Callaway. They immediately drove him eight miles from the center of town, where he was shot multiple times and left for dead.

The lynching of blacks during this period was rarely a big issue for law enforcement that was intent on maintaining the status quo at any cost, even if it meant a few blacks being killed. Callaway’s lynching, however, became a cause célèbre for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

It was the result of the persistence of a local minister, the Rev. L.W. Strickland of Warren Temple Methodist Church, who would not allow the matter to be ignored or forgotten. He immediately contacted the NAACP national office that was quick to respond, resulting in the Callaway lynching becoming a part of a national debate and movement to end lynching.

Although information was sketchy, at most, surrounding Callaway’s murder, his lynching was reported in the major print media around the country such as the New York Times and other newspapers.

Former United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall involved in Callaway case

One of the persons contacted by the Rev. Strickland was a young, aggressive lawyer, Thurgood Marshall, who later became a U.S. supreme court justice. Marshall had been an important litigator for the NAACP. He travelled around the South incognito, for the most part, investigating lynching and other crimes against blacks for the organization.

It was alleged that the Ku Klux Klan hated Marshall and placed a bounty on his head. For this reason, he barely escaped death by the Klan on one such an occasion while in the state of Mississippi. On these investigative sojourns, he would live in the homes of blacks who would provide for his safety.

Because he was in communication with the Rev. Strickland concerning the lynching of Callaway, it is not inconceivable that Marshall also travelled to LaGrange.

The social climate during this period

This was a period of time when it was perceived by some and believed by many that a select few ruled the state of Georgia. The governor at the time, E.D. Rivers, a Democrat, was such a man whose predecessor was Eugene Talmage, another powerful politician who had ruled Georgia for two terms.

It was during this period — three years earlier than the Callaway lynching — that another miscarriage of justice took place in Columbus, Georgia, less than an hour from LaGrange. Arthur Perry and Arthur Mack, two young black men, were still riddled with bullet wounds when they stood trial five days after allegedly murdering a white security guard named Charlie R. Helton.

An all-white jury deliberated only 16 minutes before convicting Perry and sentencing him to death in Georgia’s electric chair. Jurors took only five minutes to convict Mack. Both men were scheduled to die Sept. 3, 1937, slightly more than a month after Helton was stabbed to death at the Columbus fairgrounds after an argument with Mack and Perry about beer left over from a company picnic.

The NAACP quickly came to the aid of Mack and Perry, attempting to save their lives. Thurgood Marshall fired off a telegram to Georgia Gov. E. D. Rivers in protest of the sentence to no avail. Marshall did not realize it at the time, but the governor was an active member of the Klan and, during his office, regularly provided lucrative contracts to Ku Klux Klan associates.

On the other hand, Rivers was an iconoclast and, to his credit, has always been remembered as Georgia’s New Deal governor, supporting President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s programs. When Congress approved the Social Security program in 1935, Eugene Talmadge made it clear that Georgia would have nothing to do with the program.

He said “allowing blacks to retire at age 65 would damage the state’s supply of cheap labor.”

Rivers, however, embraced the New Deal, arguing that it was not charity but reparations for the North’s destruction of the South during the Civil War. With Rivers as governor, older Georgians started getting Social Security checks. But there was also the sinister side of Rivers — the corrupt Klansman side that made it possible for blacks such as Austin Callaway to be lynched with impunity.

The living relatives of Austin Callaway desire closure related to his death. If you have any information regarding this case, please feel free to contact me at gdowell@live.com.